Protecting Seagrass Flats in the Florida Keys

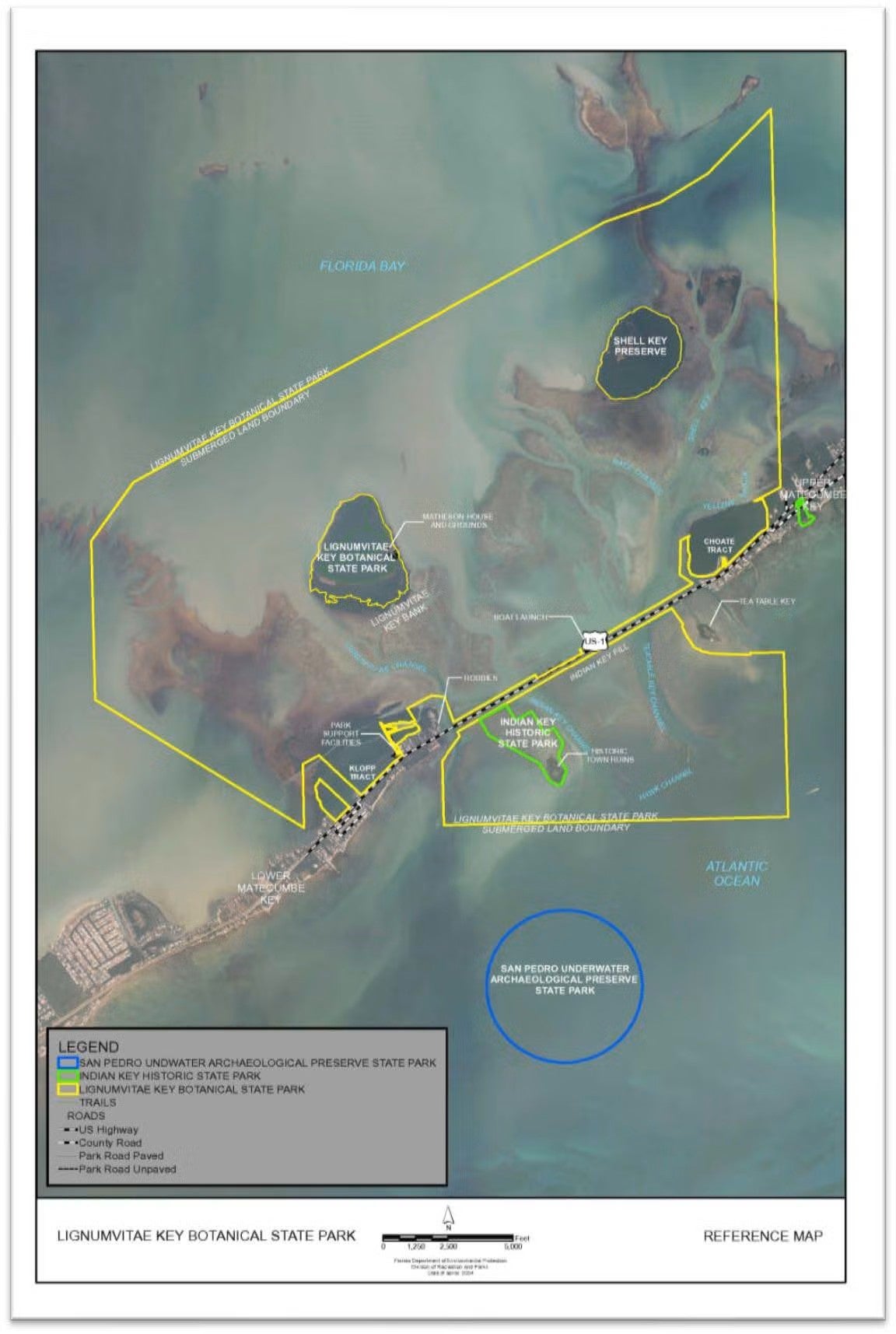

In January 2018, I started my current position as a biological scientist with the four state parks located in Islamorada, Florida (Windley Key Geological State Park, Lignumvitae Key Botanical State Park, Indian Key Historic State Park and San Pedro Underwater Archeological Preserve State Park). Each of these parks has helped broaden my overall knowledge, and each faces their own unique management challenges. No two days are alike.

In any given week, I may perform a range of tasks including non-native invasive plant surveys, maintaining cultural sites, assessing boat groundings or promoting the parks at community events.

In this issue of Biologists Tell the Story, I will highlight some of my work to manage 10,800 acres of seagrass and hard-bottom ecosystems at Lignumvitae Key Botanical State Park through the mooring buoy and channel marker program. Healthy seagrass communities are one of the most productive ecosystems in the world and are vital to the health of our coastal waters. However, this ecosystem is often overlooked for its importance.

Healthy Seagrass Flats

There are three common species of seagrass in the Lignumvitae Key Management Area: turtle grass (thalassia testudinum), shoal grass (halodule wrightii) and manatee grass (syringodium filiforme).

Despite their common names, these plants are not grasses but flowering plants that are more closely related to lilies. Seagrasses excel at removing nutrients and sediment from the water column. Each blade of grass slows water and allows sediment to settle out and nutrients to be taken up.

Seagrass grows by sending roots downward and underground stems out horizontally. These underground stems, or rhizomes, do the bulk of the work to hold sediment in place. This complex root system improves water quality by reducing erosion and preventing siltation of the water column.

In addition, healthy seagrass meadows provide habitat for thousands of different species of marine organisms. Seagrass is an important food source for large herbivores such as manatees and sea turtles as well as for the smallest of organisms that act as decomposers.

The grass itself provides a wonderful habitat for stingrays, crabs, lobsters, shrimp and countless fish species. It is no surprise that this diverse system, in turn, supports the commercial and recreational fisheries that harvest many of these species.

Unfortunately, seagrass beds are declining throughout the world. One of the major threats seagrass ecosystems face is damage from accidental boat groundings and propellers. Groundings can create scars through the beds that fragment the habitat. The scarred areas are no longer able to stabilize sediment and can erode into larger damaged areas with tidal flow. After this damage occurs, it can take over 10 years for the seagrass scar to recover naturally without restoration efforts.

Protecting Seagrass Flats

There are five deep water channels winding through the shallow seagrass flats around Lignumvitae Key. These channels are the corridors that boaters use to safely travel from the back-country waters of Florida Bay to the coral reefs of the Atlantic Ocean. However, navigating this maze of deep-water channels can be confusing even for an experienced mariner.

To protect the shallow seagrass meadows between the channels, over 100 navigational markers mark the edges of the channels. Additionally, other signage is used to delineate no-motor zone areas. These unique special-use areas are designed to allow anglers to pole and troll shallow seagrass beds for fishing while excluding motorized watercraft that could damage the seagrass. Finally, we incorporate mooring buoys in designated areas to encourage boaters to tie up watercraft at fixed points instead of using anchors.

One of my first projects with the park was to assess the damage to our navigational aids caused by Hurricane Irma in late 2017. More than half of the navigational aids and buoys were either missing or damaged from the storm. My assessment involved boating to each marker location, documenting the condition of each navigational aid, determining what supplies were necessary to make each marker whole again, and compiling GPS points.

After assessing our needs, project specifications were developed for outside contractors to complete these projects.

The navigational channel markers and buoys have all been installed and all the no-motor zone signage is repaired. With the help of the Keys Restoration Fund, we are in the last stages of approval to complete this project. It is fulfilling to be a part of team of enthusiastic individuals and watch a large multi-tiered project move forward to help protect our environment.

Also, with a generous donation from the Joseph L. and Emily K. Gidwitz Memorial Foundation, the park was able to replace 15 mooring buoys that had been lost from Indian Key, Lignumvitae Key and Shell Key during Hurricane Irma. We coordinated a great team of staff and volunteers to complete this project. It was like a treasure hunt to snorkel the areas of the missing buoys in search of the metal pins on the sea bottom that once secured these buoys. Each time we see a boat using our rebuilt moorings instead of an anchor it feels like a reward.

Finally, I am proud that park staff, volunteers and I have attended various outreach events to inform the public about seagrass ecosystems and restoration and to provide tips for navigating the local waters.

With more boaters on the water each year, the pressure on seagrass increases, even with our signage and mooring efforts. By focusing on education, I hope we can eventually stop our annual seagrass loss.

As with all park projects, the recently installed signs, mooring buoys and markers require continued maintenance. Park staff report damaged or missing markers, and in-house workdays are scheduled as the need arises. It is a great team effort to maintain these resources, and I am thankful to work with such professionals.

About the Author

A Florida native, Becky Collins grew up exploring her backyard of Central Florida. Being immersed in nature from an early age led her to follow her passion and pursue a degree in Wildlife Ecology and Conservation from the University of Florida. After college, Becky worked as a program specialist and environmental educator in central Georgia, but her passion for Florida ecosystems brought her home to pursue a career with the Florida Park Service.

Becky has been with the Florida Park Service since 2013, first working as a park ranger at John Pennekamp Coral Reef State Park and then as a park programs specialist with the Florida Keys Overseas Heritage Trail.

Collins now works as a park biologist in the Islamorada Area State Parks, which includes, Lignumvitae Key Botanical State Park, Windley Key Fossil Reef State Park, Indian Key Historic State Park and San Pedro Underwater Archeological Preserve. Her focus includes seagrass restoration, invasive plant management, cultural resources, outreach and education.

About the Biologists Tell the Story Series

In this series, we will learn a little more about our biologists as they share stories of their work in Florida’s state parks. The leadership and scientific research park biologists provide is essential for Florida's legacy of conservation and land management. This series is an opportunity to connect these projects to the places where we ensure the health and sustainability of Florida State Parks.