History of BulowVille

The early 1800s marked a turbulent era in Florida’s history as settlers established plantations on lands that the Seminole Indians believed to be theirs.

In 1821, Major Charles Wilhelm Bulow - a wealthy merchant from Charleston, South Carolina - acquired 4,675 acres of wilderness bordering a tidal creek that would bear his name.

Naturalist John James Audubon came to Bulowville on December 25, 1831, in search of birds for his book “Birds of America.”

Audubon wrote of the hard rowing in salt marshes, difficulty wading in mud, and fighting sand flies and mosquitos. Audubon used BulowVille as a base for trips to find birds.

On one trip he traveled to the McRae plantation near the Tomoka River and on to Spring Garden, which is now De Leon Springs State Park. He wrote that he was well-treated at BulowVille and enjoyed staying there.

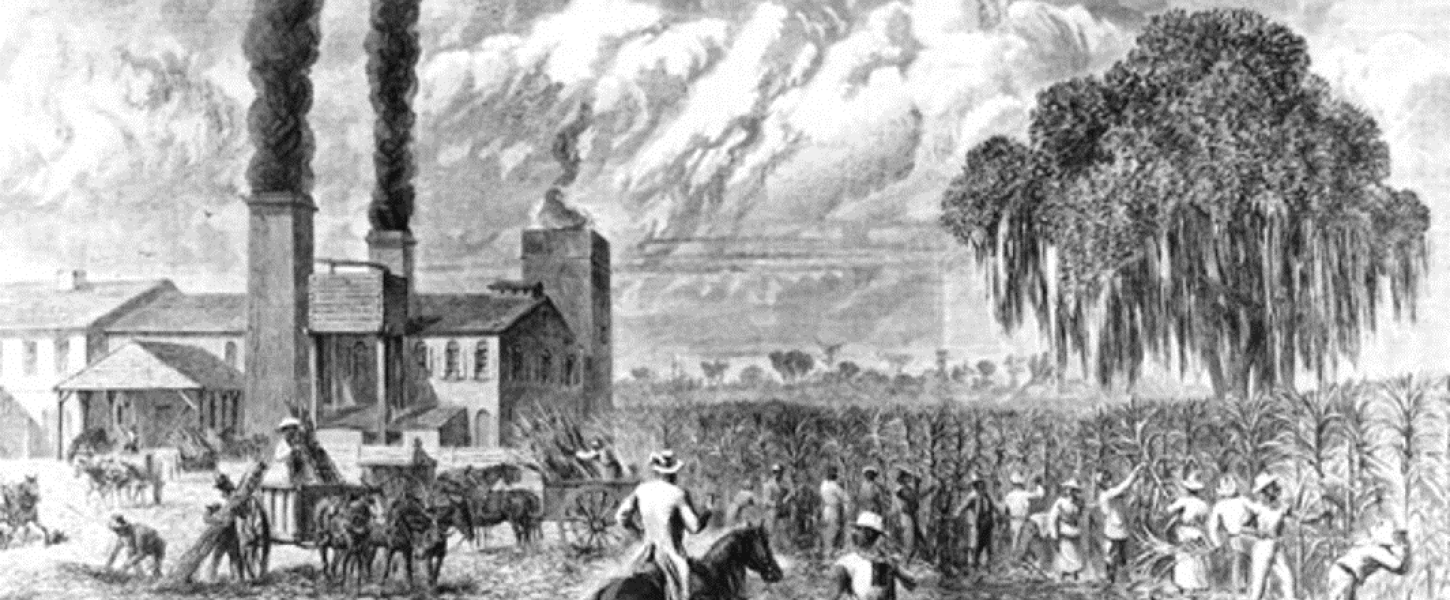

Using slave labor, Major Bulow cleared 2,200 acres and planted sugar cane, cotton, rice and indigo.

Soon after the plantation was established, Major Bulow died at age 44, leaving his holdings to his only son, John Joachim Bulow. John inherited BulowVille as a young teenager. John J. Bulow was raised and schooled in Paris, France, from the age of five, until he left France for BulowVille.

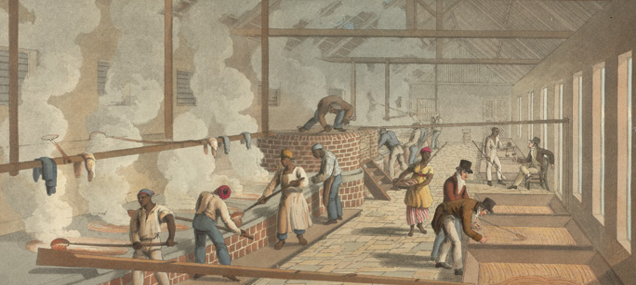

In the late 1700s, growing world demand for commodities such as rice, cotton and sugar brought the plantation economy to East Florida. These large operations thrived by using the forced labor of enslaved Africans.

The 46 cabins were home to 197 men, women and children who were documented in the 1830 census. Cabins were arranged in a semi-circular pattern around the main plantation house.

The 12- by 16-foot buildings had shingled roofs and wood siding. Each dwelling had a coquina fireplace for warmth and cooking. In comparison, the main house was a French Colonial style mansion. The cabin area was a place of community for the slaves. Slaves created and sang songs to relay hidden messages. Slave resistance came in work slowdowns and faked illnesses.

Daily work at BulowVille consisted of:

- Maintain machinery and farm implements.

- Plant, grow, harvest and process sugar cane, rice and cotton crops.

- Feed and clothe workers.

- Take care of all plantation animals.

- Build all equipment and buildings.

Under the management of overseer Francisco Pellicer Jr., production increased and the plantation prospered until the outbreak of the Second Seminole War.

John Bulow did not agree with the U.S. government’s intentions to send the Seminoles to reservations west of the Mississippi River.

He demonstrated his disapproval by firing a four-pounder cannon at Major Putnam’s command of State Militia as they entered his property.

Troops took Bulow prisoner. After a brief campaign against the Indians and with most of the troops ill, Major Putnam’s command relocated to St. Augustine and allowed Bulow to go free.

Realizing that the Seminole nation was becoming more hostile, young Bulow, like other settlers and their slaves, abandoned his plantation and followed the troops northward.

Around January 11, 1836, the Seminoles burned “Bulowville,” along with other plantations in the area. Abandoned January 23, 1836, a "great rosy glow" was observed on January 31, 1836, in St. Augustine.

The house and furniture were valued at $5,000.

The house was never rebuilt. John Bulow, discouraged by the destruction, died three months later at the age of 26 and was buried in St. Augustine.

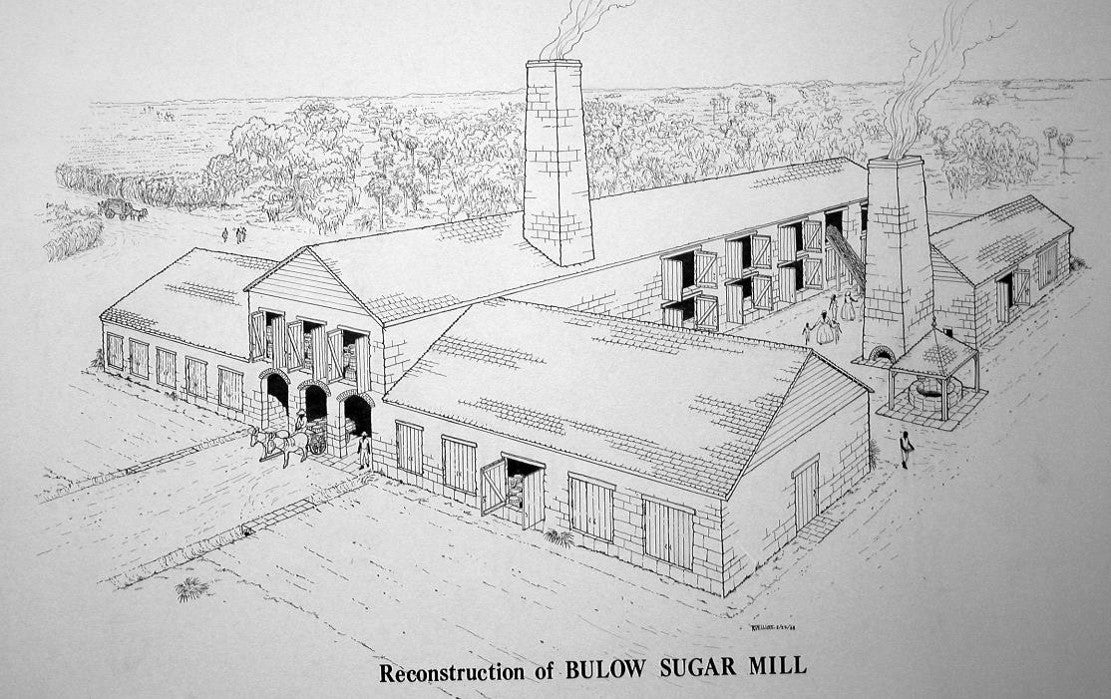

All that is left today of this plantation are the coquina ruins of the sugar mill, several wells, a spring house and the crumbling foundation of the mansion. The cleared fields have been reclaimed by the forest, and the area looks much as it did when it belonged to the Seminoles.