Digging into the Past

Two common question from visitors to the park are “When was the last dig here?” and “When will you be doing another one?” Thanks to advancements in technology, digging through the layers of shell and sand isn’t as essential as it once was. Excavation is used when modern technology reveals a question that can be answered only through the disturbance of “digging in the dirt,” but this wasn’t always the case.

The first documented discovery of the Crystal River mound was by Clarence Bloomfield Moore (aka CB Moore) in 1903. Moore was a collector, an antiquarian or, as referred to in early literature, a “gentleman archaeologist.” Moore knew from previous discoveries that aboriginal populations frequently built their villages and ceremonial centers near or on the coastline of Florida.

On a boat aptly named the “Gopher,” Moore and a small crew traveled up and down the Florida coast looking for elevated spots to explore. The towering mound of shell at Crystal River was overgrown but still visible from river, and it attracted Moore’s attention. Upon further investigation, Moore found the undisturbed sand burial mounds and two more shell midden mounds. For seven days Moore and his men excavated the burial mounds, removing numerous funerary goods.

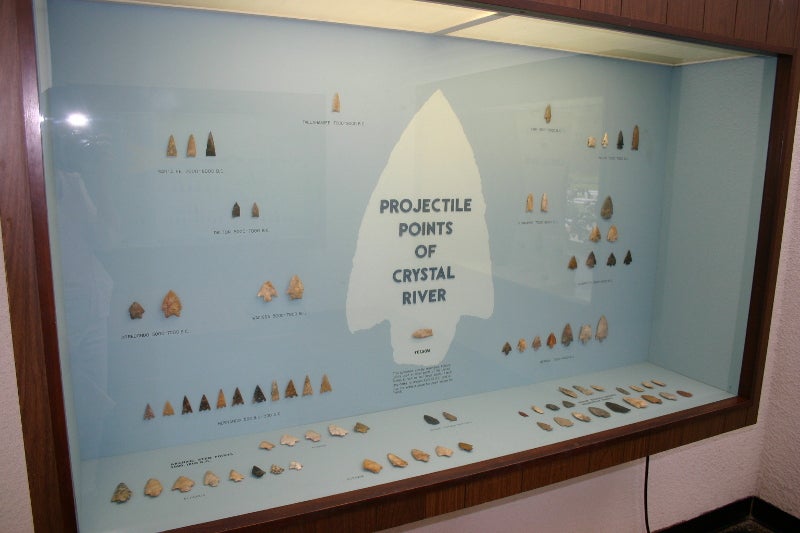

Copper ear spools, plummets’ of shell, coral, soapstone pipes, incised pots, bone awls and fish bone arrowheads were all well-documented by Moore, although unfortunately his notes did not include information on the location of these artifacts within the mound that a modern archaeologist would include. The collection of artifacts found by Moore at Crystal River were transported and then sold to museums in Pennsylvania and Massachusetts, and many of the artifacts remaining from his excavation of the site currently reside at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian.

The second person to perform a major study of the site was Ripley Bullen. Beginning in 1950 and working off and on for the next 15 years, Bullen was able to prove the site was in use during the Deptford, Swift-Creek and Weedon Island archaeological periods. Ripley Bullen’s work in his role as the state archaeologist exposed the significance of the site and the need to protect it for future generations. His working relationship with the landowners and commitment to preserving the site was also the driving force that enabled the site to become a Florida State Park.

In 1962 the state finally acquired the land, and Bullen went to work. He supervised the clearing and construction on the site, ensuring the heavy equipment did not damage important features. During this construction, Bullen found more mounds and two stelae, important archaeological stone slabs. These findings are all on display at the Crystal River Archaeological Museum, which has exhibits detailing the process that occurred here.

In the future archaeologists may need further exploration to answer some of the more specific questions that Crystal River Archaeological State Park holds, but only time will tell.